Hot Springs, Arkansas: Gangsters and Bootleggers

Who knew hot springs, mineral water, bootleggers and gangsters could all be woven together?

Downtown Hot Springs

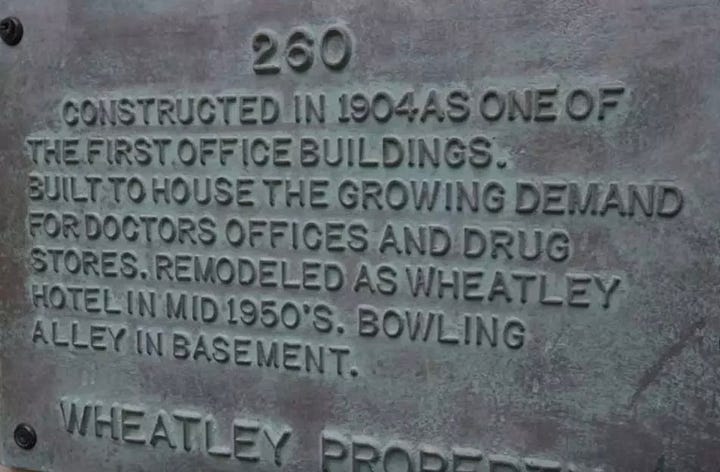

Hot Springs is named for the thermal underground mineral water springs. Beginning in 1832, bathhouses began popping up in Hot Springs, Arkansas due to the abundance of natural hot springs at the base of Hot Springs Mountain.

It was thought that the hot springs had healing properties and that by bathing in them, illnesses could be healed or prevented. It was also about rejuvenating the mind and spirit.

Over the years there were several versions of bath houses but the ones still in existence, the ones you can visit, were built between 1892 and 1923.

It was also around this time that Hot Springs became known as America’s First Resort Town.

Established in 1832 as the country’s first national “reservation,” Hot Springs eventually became a national park in 1921 by congressional act. It’s the oldest managed park within the U.S. National Parks System (NPS).

Today, Hot Springs National Park is the only park in the system surrounded by a city.

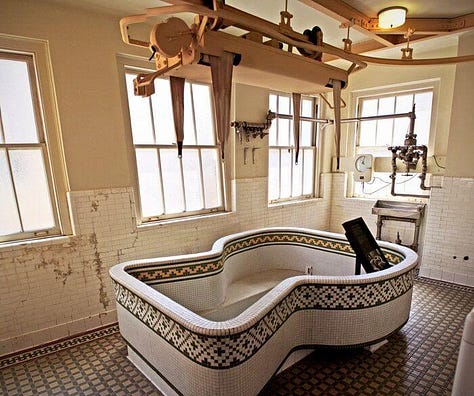

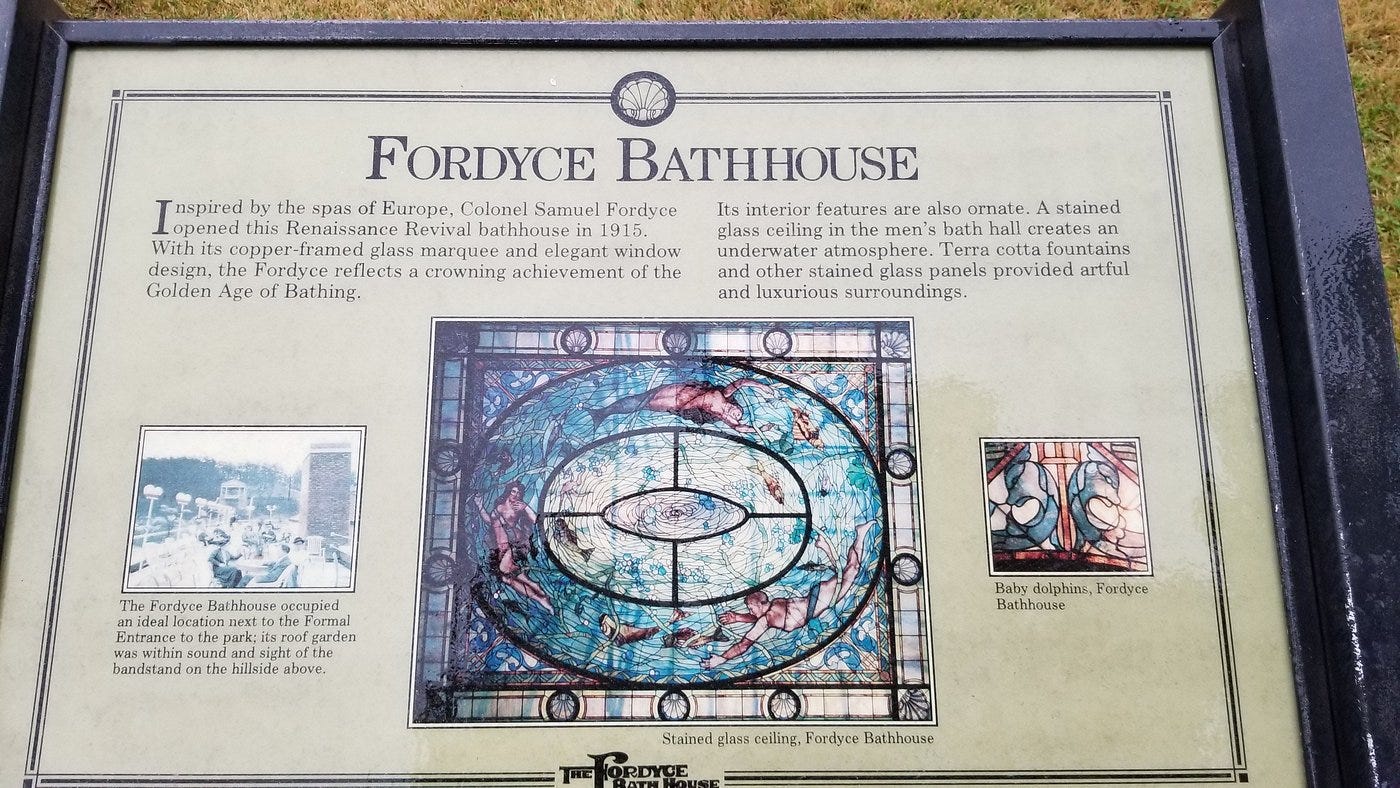

The Fordyce Bath House

In the first half of the 20th century, The Fordyce Bath House was one of the most decadent of all the therapeutic bath houses along Bathhouse Row in Hot Springs. Three floors of an era gone by where glamour and opulence were the priority of the day.

As water therapies suffered a rapid decline in the 1950’s, the Fordyce, along with most of the others bath houses, went out of business and fell into disrepair. The National Park Service stepped in and beautifully restored the Fordyce to its original state and is now using it as the visitor center and free museum for the National Park.

Hot Springs National Park is on federal land. So, the eastern side of Central Ave where the bathhouses are located is part of the park.

The other side of the street is not considered part of the national park, it is state land.

It was this bit of geography that attracted another element to Hot Springs.

In 1917, the 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution, which prohibited the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors,” was drafted and passed national legislation the following year. Called the “noble experiment” by Herbert Hoover, 75% percent of the states approved the amendment, which was ratified on January 16, 1919.

In 1920, the Volstead Act was passed to enforce the amendment.

The National Prohibition Act, known informally as the Volstead Act, was an act of the 66th United States Congress designed to execute the 18th Amendment (ratified January 1919) which established the prohibition of alcoholic drinks. The Anti-Saloon League's Wayne Wheeler conceived and drafted the bill, which was named after Andrew Volstead, chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, who managed the legislation.

The Volstead Act had a number of contributing factors that led to its ratification in 1919. For example, the formation of the Anti-Saloon League in 1893. The league used the after effects of World War I to push for national prohibition because there was a lot of prejudice and suspicion of foreigners following the war. Many reformers used the war to get measures passed and a major example of this was national prohibition. The league was successful in getting many states to ban alcohol prior to 1917 by claiming that to drink was to be pro-German and this had the intended results because many of the major breweries at the time had German names. Additionally, many saloons were immigrant-dominated which further supported the narrative that the Anti-Saloon League was pushing for. Another factor that led to the passage of the Volstead Act was the idea that in order to feed the allied nations there was a greater need for the grain that was being used to make whiskey. Prohibitionists also argued that the manufacture and transportation of liquor was taking away from the needed resources that were already scarce going into WWI. Wikipedia

With World War I ending and the nation in high spirits, the demand for liquor quickly increased. Another culture emerged for those who saw an opportunity and financial gain in thwarting the new law and filling the public demand. Bootleggers, illegal alcohol traffickers, and speakeasies began to multiply by the hundreds.

The “cocktail” was born then, virtually non-existent before Prohibition.

Speakeasies, illegal taverns that sold alcoholic beverages, came to an all-time high during the Prohibition era in the United States from 1920 to 1933. These bars, also called blind pigs or blind tigers, were often operated by organized crime members.

They were located on the “state side” of Central Avenue in Hot Springs.

Al Capone

When I sell liquor, it’s bootlegging.

When my patrons serve it on a silver tray on Lakeshore Drive, it’s hospitality.

Al Capone

Joining their ranks was Al Capone, who arrived in Hot Springs hoping that the thermal waters and bath house treatments would cure his syphilis.

The gangsters would stay on the “state side” of Central avenue and travel through underground tunnels to the bath houses on federal land so they couldn’t be apprehended by federal agents.

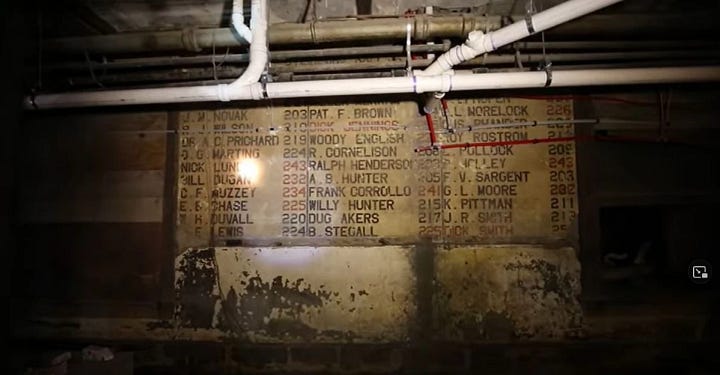

Not only did they have tunnels to the Speakeasies, you’ll learn at the Gangster Museum, they had a bowling ally underground as well.

Capone soon discovered that his Chicago business could grow exponentially with the addition of some moonshine distribution out of Hot Springs.

With Joe Kennedy (famous father of JFK and unconfirmed but strongly suspected bootlegger) on board, he needed a means of transportation to increase distribution.

Staring at a case of Mountain Valley Spring Water, he came up with the idea to turn the labels upside down and attach them to moonshine bottles. In this way, he was able to ship mass quantities of what looked like water bottles on railroad cars and easily identify the moonshine upon arrival.

Soon, he purchased an underperforming dairy outside of town and turned it into his own moonshine distillery. Capone placed his moonshine in clear glass bottles and called his product Mountain Valley Water. He would then smuggle his bootleg liquor in tanker railroad cars.

Mountain Valley Spring Water

1871, Mountain Valley Spring Water was originally known as Lockett’s Spring Water, until pharmacist Peter E. Greene and his brother, John Greene renamed the mineral rich spring water Mountain Valley. Ownership of the spring was transferred in 1902, when August Schlafly of St. Louis, Missouri, and his family became sole owners.

By the 1920s, Mountain Valley Water was being served in the United States Senate.

In 1924, Schlafly purchased the DeSoto Springs Mineral Water Company, located at 150 Central Avenue in Hot Springs. The two-story, classical revival brick building was built specifically to house a mineral water depot. A third level was added in 1921 to house a Japanese-themed dance hall with accommodations for a live band. The building remained the DeSoto Spring Water Depot and DeSoto Dance Hall until 1936, when Mountain Valley Water Company made the building its national headquarters and visitors center.

One might wonder how Hot Springs came to be a center for bootlegging and other illegal activities.

This activity was sheparded by Leo McLaughlin.

In 1926, Leo McLaughlin was elected mayor. He fulfilled a campaign promise to run Hot Springs as an “open” town, which included legal gambling and overlooked hotels that advertised the availability of prostitutes, and off-track booking was available for virtually any horse race in North America.

As mayor, McLaughlin reigned as the undisputed boss of Garland County politics for the next 20 years. However, McLaughlin took it to a new level, using voter fraud and other unlawful tactics to drive his political machine.

Between 1927 and 1967, Hot Springs operated the most considerable illegal gambling racket in the country.

During McLaughlin’s time in office, many underworld characters frequented Hot Springs’ spas, and gambling became one of the town’s most popular forms of entertainment.

These infamous names included Owen Vincent “Owney” Madden, Bugs Moran, Charles “Lucky” Luciano, and Al Capone.

A few of their favorite hangouts were the Southern Club, which now houses Josephine Tussaud’s Wax Museum; the Ohio Club, now considered to be the oldest bar in Arkansas; the Arlington Hotel, which still entertains guests; and the Oaklawn Race Track, which is still open today.

When you drive through Hot Springs you would never know the history unless you stopped and looked around.

If you’re going to stop in Hot Springs, the Gangster Museum is a wealth of information surrounding the history of Hot Springs. It’s an hour and half guided tour loaded with history encompassing the gangsters, bootlegging, Hot Springs history and baseball history.

Who knew hot springs, mineral water, bootleggers and gangsters could all be woven together?

Great essay

Some interesting history! Wonderful that the National Park Service has restored the baths. Very elegant!