The Forever Gift II: Teach Reading Early

It wasn’t until he asked me how to pronounce a smallish word that I realized he didn’t know how to sound-out words.

NOTE: As we get into the gift giving season, please enjoy this post I wrote and distributed in November, 2022.

I had a child that could read chapter books in kindergarten.

And while his peers were struggling to read in first and second grade, he was able to read out loud, the Harry Potter books to his classmates. (I pulled him out of a private school near the end of second grade for a myriad of reasons, see my Homeschooling series if you’re curious.)

Experts say that most children learn to read simple picture books with words at age 6 or 7, meaning first or second grade.

I guess I was lucky my kiddo somehow learned how to read when I wasn’t looking. He never could explain to me how he learned to read, I guess I didn’t ask the right questions.

I surrounded him with all levels of books within his reach, from an early age.

We went to the public library in most cities we visited to spend time looking at books.

The local bookstore was also an absolute favorite outing.

Book stores in the places where we traveled were also great fun; I remember the original bookstore in Bequia (part of Saint Vincent and the Grenadine islands in the Caribbean) as one of our destinations.

I imagine that somehow he learned to read because of this, and the idea that I read to him constantly, pointing at, sounding out, and pronouncing the words for him.

I remember when he was in preschool, he told me they had “baby” books at school.

That should have been an early clue as to how advanced he was.

I used to write a blog about traveling while homeschooling called Traveling With The Kid, mainly to demonstrate journaling for my student. So when we traveled, I required “The Kid” to keep a journal. This is an entry from around age twelve:

Our day in Martinique was a "town day". We just goofed around town and looked in shops. We saw the Martinique library it was very neat inside. There were a lot of old books high up on shelves. I imagined them to be the old leather kind, because we couldn't really pick them up to look. They probably were written in French. I am learning French and my mom reads some French, mostly technical stuff - and food and cookbooks! We think we can get by in French towns!!!

My kiddo has always had an interest in books.

He wanted to see the library in Martinique (in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, Caribbean).

It was pretty impressive.

It wasn’t until he asked me how to pronounce a smallish word that I realized he didn’t know how to sound-out words, even though I thought he could. This was just after I pulled him out of school near the end of second grade.

Now I have to admit, the word didn’t follow any phonetic rules I was aware of, but it was an opportunity to expand the reading abilities.

The word he wanted to pronounce was “colonel”. When I told him it was pronounced “kernel” he was perplexed.

Many questions followed.

I introduced the idea of phonetics.

He was intrigued.

I told him I would teach him phonics.

I started his phonics education with easier words than “colonel”.

Decades before “Common Core” became a controversial term in education policy, in the late 1970’s, E.D. Hirsch, suggested that there was a core body of knowledge that students need to acquire. That body, he suggested as “Core Knowledge”, where the more students know, the more they are able to learn (One of the Core Knowledge’s mottos is: “Knowledge builds on knowledge.”).

I agree with this idea and this is how I built our homeschool, but also a lifelong love of books for my student.

Knowledge builds on knowledge.

Phonics is a part of the core body of knowledge students need to acquire.

But phonics isn’t widely taught in American public schools these days, and I feel it is the reason many American children can’t read at grade level.

My former public school district, the urban one, that I funded over the years with many tax dollars, recently announced that their third graders couldn’t pass the third grade reading proficiency test.

Their answer?

Lower the standards.

The majority of schools in the United States, use an approach to reading instruction called “balanced literacy”. In 2019, a national survey done by EdWeek Research Center found that about 72% of American educators report using balanced literacy to teach reading.

One of the reasons for its popularity is its openness to interpretation.

Balanced literacy can be understood as a “little bit of everything”. Balanced literacy in practice usually means the “whole language” approach to reading. But because it may or may not include phonics, it doesn’t work for all students. Some say balanced literacy will only help 30% of students become successful readers.

What is whole language approach to reading?

A whole language approach to teaching reading was introduced in the 1800s through Horace Mann, a politician, who is today widely known as “the father of American education.” Mann warned against teaching children to sound out words letter by letter because he thought it would distract them from the meaning of the word.

By the 1950s, many American public school children were receiving whole language instruction and it was solidly grounded in primary schools by the late 1970s.

Whole language approach is centered on memorizing sight words and connecting them to every day life. A whole language approach doesn't argue against the importance of phonetics, it simply states it is not all that should be included in reading instruction.

In 1955, Rudolf Flesch published a book called Why Johnny Can’t Read—and What You Can Do About It. This book, the first to oppose whole language, claimed that the lack of explicit phonics instruction in American schools prevented children from learning to read properly. He revealed that the average American third-grade student was “unable to decipher 90% of his own speaking and listening vocabulary” when they saw it written on paper.

I read recently, that now the education wonks are coming back around to teaching phonics and word decoding.

It’s a new fangled thing called the “Science of Reading”.

What’s Science of Reading?

The Science of Reading is a body of research that answers the question: “How does the human brain learn to read?”

And guess what?

It suggests learning to read phonetically is most effective.

McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers

My student was interested in being able to decode words, especially when I put it that way. He had a love of spy and detective stuff then, and up to this day. Decoding was just what he wanted to be able to do.

He couldn’t wait to see “colonel” decoded.

I started with McGuffey's First Eclectic Reader. I warned, it was a series of “baby” book stories that showed how to decode the simple words he already knew.

He was game.

What are McGuffey’s Eclectic Readers?

The McGuffey’s Readers are a set of academic textbooks that were used originally in United States schools starting in 1836 up to the late sixties. They teach how to read using phonics. Phonics follows a bottom-up approach (letters and sounds before words).

I learned to read using the The McGuffey’s Readers.

In the nineteenth century, The McGuffey Readers became cornerstones in establishing America’s moral values. The books were not overtly religious but they did stress religious values and emphasize moral lessons intended to develop students into good citizens. Some had accused The McGuffey Readers of being anti-Semitic and anti-Catholic, but McGuffey later revised them, thus the “revised editions”. The material includes words, phrases, poems and stories illustrated with phonetic spellings that combine the moral, and ethical principles.

McGuffey readers are no longer popular in American schools as they were in the nineteenth century.

Imagine that.

What I liked about the readers was the visual phonetics at the first part of the lesson(s). It gave me an opportunity to explain how words got “decoded”.

What my student liked was how easy it made it to look at new and bigger words.

A favorite quote from a favorite movie scene:

Elizabeth: Captain Barbossa, I am here to negotiate the cessation of hostilities against Port Royal.

Barbossa: There are a lot of long fancy words in there Missy; we're naught but humble pirates. What is it that you want?

Elizabeth: I want you to leave and never come back.

Barbossa: I'm disinclined to acquiesce to your request…..

Barbossa: Means "no".

Elizabeth Swan and Captain Barbossa, Pirates of the Caribbean.

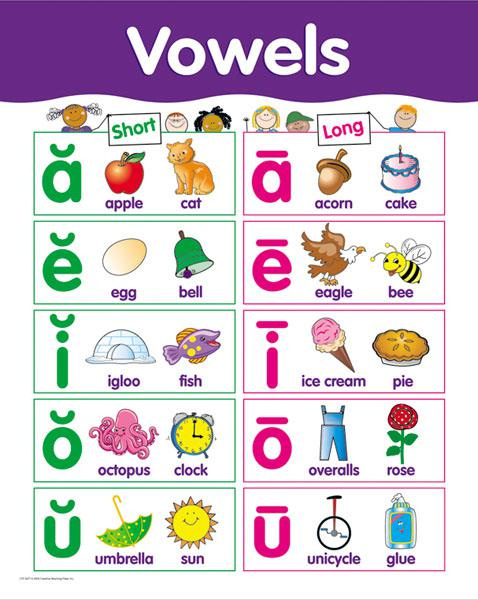

My student was well beyond the stories in the series of Readers books, but still found them very useful. I handed him a vowel chart, similar to what is pictured above as a cheat sheet, and the McGuffey’s Eclectic Spelling Book (Free .pdf copy here) because it was pretty key to using the series.

McGuffey’s Readers do involve a teacher at first.

In our case, I explained how to use the vowel chart, but also went through the McGuffey’s Eclectic Spelling Book pointing out items I felt pretty sure he’d get hung up on, or ignore all together. Also, at that time, I showed him a dictionary and explained how to use it. He liked how the three tools he had were all tied together and could be used for what he wanted to achieve.

I would occasionally have pop up spelling and vocabulary quizzes just to see if he was really understanding what he was learning on his own.

He was.

As we were eclectic/unschoolers, he could pick up the books whenever he wanted and he did quite frequently in the first few weeks with them. He used the Primer and 1st Reader in the order prescribed by the author. He skipped the 2nd Reader because his reading level was well beyond most of the material included. This was at age eight (beginning to mid “third grade” level) (we didn’t really use grade levels, but when I try to explain what we did, I try to relate it to a grade level).

The 3rd Reader got into grammar. He skipped this one because he wanted to move on to the 4th Reader. We didn’t get back to grammar until our “fifth grade” (age eleven) and we used a combination of McGuffey’s as reference, and Steck Vaughn workbooks.

Grammar was not of huge interest to my student but he did finally master it.

In case you were wondering, we did do standardized testing each year because of state homeschooling requirements, but also because we were both curious if he could pass a “grade level” standardized test.

He could.

We used the CAT/5 Survey each year for the “grade level” he would have been in and my student had perfect scores in all English/language arts sections each year. (The California Achievement Test, 5th Edition Survey (CAT/5 Survey) is a nationally normed standardized test originally published in 1992 by CTB/McGraw Hill.)

When it came time, he had perfect scores in English and reading on the ACT (college admissions test) and perfect scores on the Critical reading portion of the SAT (college admissions test).

I attribute these achievements to the work he did early on using the The McGuffey Eclectic Readers.

The McGuffey Eclectic Readers are numbered according to age or reading levels, not grade levels. I put grade levels in parentheses for reference in the chart below. Where one begins will depend on the reading level of the child, but also on how they learn and the interest level of the subject matter.

Age 6 (Grade K-1): McGuffey Primer. This book begins with the alphabet, moves to simple one-syllable words. (Free .pdf copy here)

Age 7 (Grades 1-2): McGuffey 1st Reader. Most words in this reader are phonetically presented. (Free .pdf copy here)

Age 8 & 9 (Grades 2-3): McGuffey 2nd Reader. This book begins with one and two syllable words and progresses to more difficult words. (Free .pdf copy here)

Age 10 & 11 (Grades 3-4): McGuffey 3rd Reader. This book develops thinking skills and richer vocabulary, it is the beginning of grammar (the study of the classes of words, their inflections and their functions and relations in the sentence.)(Free .pdf copy here)

Age 12 & 13 (Grades 4-6): McGuffey 4th Reader. This book develops advanced vocabulary and thinking skills and introduces some of the greatest English authors including Webster, Jefferson, Shakespeare. (Free .pdf copy here)

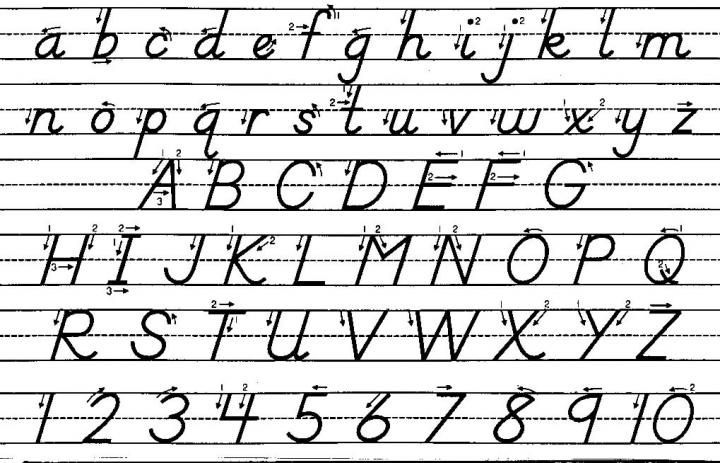

In most lessons of a McGuffey reader was an element of handwriting and/or penmanship. The first time my student saw “slate work”(students in the nineteenth century wrote on pieces of slate (A fine-grained metamorphic rock that splits into thin, smooth-surfaced layers.) with chalk) he laughed. He knew what it meant from some of his reading, but we had already been working on D'Nealian Handwriting with beginning journaling, so he wrote some of the practice stories with the readers using D'Nealian.

What is D'Nealian Handwriting?

D'Nealian Handwriting is a method of teaching cursive and manuscript English handwriting. The font was designed by a primary school teacher, Donald Thurber, in 1978. It was introduced as an alternative to address the difficulties faced by some children learning the traditional script method. I used it to alleviate difficulty transitioning from printing letters to cursive writing.

Learning to read and learning how to write go together. Writing is also a part of the core body of knowledge students need to acquire.

My student finally decoded “colonel”. He gave an explanation similar to the following.

col·o·nel (kûr′nəl). Noun.

“Colonel” is pronounced just like “kernel”.

How did this happen? From borrowing the same word from two different places.

The word “colonel” stems from the Italian word “colonnello”, which, in turn, was derived from the Italian word “colonna” meaning “column”. This was because the rank was bestowed upon the commander of a column of troops.

This word was then adopted by the French, who translated the term in their own language, converted the word “colonnello” to the word “coronel”.

The French “coronel” made its way into English, in the late sixteenth century when scholars started producing English translations of Italian military treatises. Under the influence of the originals, people started spelling it “colonel”.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, the spelling had standardized to the “l”version.

“Colonel”.

Before students can truly develop a love of reading, and before they can read to learn, they first must learn to read.

If you have a second or third grader who is struggling to read, I highly suggest both of you spend some time looking at The McGuffey Eclectic Readers. They aren’t like anything either of you have seen (I bet) and may just help you develop for them, a lifelong love of books.

It’s one of the greatest things a parent can give to a child, a lifelong love of books.

It’s a forever gift.

We used physical books, which adds to the love of books in my opinion. Here are links to Amazon for hard copies if you find the .pdfs difficult to use:

McGuffey’s Eclectic Spelling Book

If you’re not so sure about the McGuffey’s readers here’s another effective resource:

Why Johnny Can't Read: And What You Can Do about It by Rudolf Flesch.

More:

Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation by Lynne Truss

An excellent Scientific explanation about teaching phonics and beginning reading here:

by:

“Lower the standards” seems to be the standard procedure these days, this makes me so sad. We have a generation who thinks they are the best and brightest ever and yet they are as fragile as a leaf in the wind.

I learned to read using McGuffey.

1955 and I was five. It worked for me. This was a home schooling event. But disciplined. We had class every morning in the "class room."